undefined

undefined

Post-pandemic, most Americans who can want to continue working from home, Pew study finds

K.C. Alfred, TNS

Lucas Fernandez of La Mesa, Calif., is working a hybrid model where he works at home part of the time and at the office other times. A new study by Pew Research Center found most people now teleworking from home want to continue to do so after the pandemic abates.

Most Americans now teleworking from home want to keep doing so, with more than half saying they would work remotely after the pandemic, a new Pew Research Center report finds.

The national survey of U.S. adults reveals that while the coronavirus may have changed the location of our jobs — whether in an office or from home — it hasn't significantly reshaped our work duties and culture for a majority of employed adults.

"Another third said they'd want to work from home some of the time. A very small share want to go back to the office full-time," said Juliana Horowitz, associate director of social trends research at Pew Research Center and one of the co-authors.

As for meeting on web platforms, "a majority see that as a good substitute for in-person contact," Horowitz said. "We don't see 'Zoom fatigue' in our survey." Videoconferencing and webinar fatigue showed up among an estimated 37% of those surveyed, she said.

Among workers who remained in the same job but shifted to remote work, more than 60% are as satisfied as before the pandemic and saw no change in productivity or job security.

Those working from home all or most of the time now see clear upsides with telework. About half (49%) of Americans now have more flexibility to choose when they put in their hours, and 38% say it's easier to balance work with family responsibilities.

Still, for most Americans (62%), jobs can't be done from home. And that's exposed a clear class divide between workers who can and cannot telework.

Those working from home mostly have college degrees, about two-thirds with a bachelor's degree or beyond. That compares with only 23% of those without a four-year college degree working from home.

Similarly, while a majority of upper-income workers work from home, most lower- and middle-income workers cannot. The Pew Research Center survey of 10,332 U.S. adults was conducted between Oct. 13 and 19.

The analysis was based on 5,858 adults among the respondents who are working part-time or full-time and who may have multiple jobs but have only one position they consider their primary employment.

Workers' ability to do their job from home varies by industry. Americans in information and technology sectors (84%); banking, finance, accounting, real estate, or insurance (84%); education (59%); and professional, scientific, and technical services (59%) can mostly work from home.

Public-facing workers and front-line employees such as restaurant staff, nursing and health care, police and fire, and waste management aren't so lucky.

About three-quarters or more of those employed in retail, trade, or transportation (84%); manufacturing, mining, construction, agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (78%); and hospitality, service, arts, entertainment, and recreation (77%) say their jobs can't be done from home. Two-thirds of those in the health care and social-assistance sector say the same.

Among those in government, public administration, or the military, the divide is roughly even: 46% say their job can be done from home and 54% say it cannot.

Also, the pandemic has exposed an age gap in virtual work.

Among those working from home, Americans 50 or younger are significantly more likely to say it's been difficult for them to get their work done without interruptions (38% for workers ages 18-49 vs. 18% for workers 50-plus and older). The youngest workers in the survey are among those most likely to say they lack motivation: 53% of those ages 18-29 years.

Men and women who can work from home are about equally likely to say they'd want to continue after the pandemic. Women are more likely than men to want to work from home all of the time (31% vs. 23%).

That's the case whether they have minor children or not. In fact, the shares of workers with or without children below 18 who say they would work from home permanently are nearly identical.

"Women are more likely to want to work from home. Period," she said.

When it came to balancing work and family, parents with young children found it harder to do so, "and mothers, in particular, much more than fathers."

Among employed adults with some college or less education who say they can do their job from home, 60% say they would want to work from home all or most of the time post-pandemic, compared with half of those with at least a bachelor's degree.

"For those who can't work from home, there are big differences about concerns about exposure to the virus and unknowingly exposing others and their families," she said.

Poll: Americans Like Working at Home

Most of those working remotely would still prefer to work from home when states begin to lift coronavirus restrictions.

A new Gallup found that 56% of U.S. workers were “always” or “sometimes” working remotely in January.(Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

A majority of Americans work remotely in order to avoid contracting the coronavirus nearly a year after the outbreak was declared a global pandemic and life around the world dramatically changed.

A new Gallup found that 56% of U.S. workers were "always" or "sometimes" working remotely in January. The percentage of workers punching in from home hit a high of 70% in April. It has declined with each subsequent month before leveling out at 58% in September for four months.

Cartoons on the Coronavirus

As the number of COVID-19 cases began increasing in the U.S. states implemented restrictions and entered lockdowns, permitting only essential workers to report to work in person.

The decline is mostly due to Americans reporting that they are "always" working from home. In April, 52% of adults reported always working remotely. It declined to its lowest point of 33% in September and has held steady since then, with that same percentage reporting always working from home last month.

Americans reporting "sometimes" working remotely has ranged from 18% in April to 23% in January.

The percentage of Americans reporting "never" working remotely rose from 31% at the start of the pandemic in April to a high of 44% last month.

Forty-four percent of those working remotely said they would still prefer to work from home when states begin to lift restrictions because of personal preferences. Thirty-nine percent said they would want to return to working in an office, a number that has increased since a low of 28% in July.

Still, even as restrictions are lifted, 17% of Americans would still prefer to work from home because of concerns about the coronavirus.

How the Coronavirus Outbreak Has – and Hasn’t – Changed the Way Americans Work

About half of new teleworkers say they have more flexibility now; majority who are working in person worry about virus exposure

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand how the work experiences of employed adults have changed amid the coronavirus outbreak. This analysis is based on 5,858 U.S. adults who are working part time or full time and who have only one job or have more than one job but consider one of them to be their primary job. The data was collected as a part of a larger survey conducted Oct. 13-19, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology.

Terminology

References to workers or employed adults include those who are employed part time or full time and who have only one job or have more than one job but consider one of them to be their primary job.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree.

“Middle income” is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for panelists on the American Trends Panel. “Lower income” falls below that range; “upper income” falls above it. See the methodology for more details.

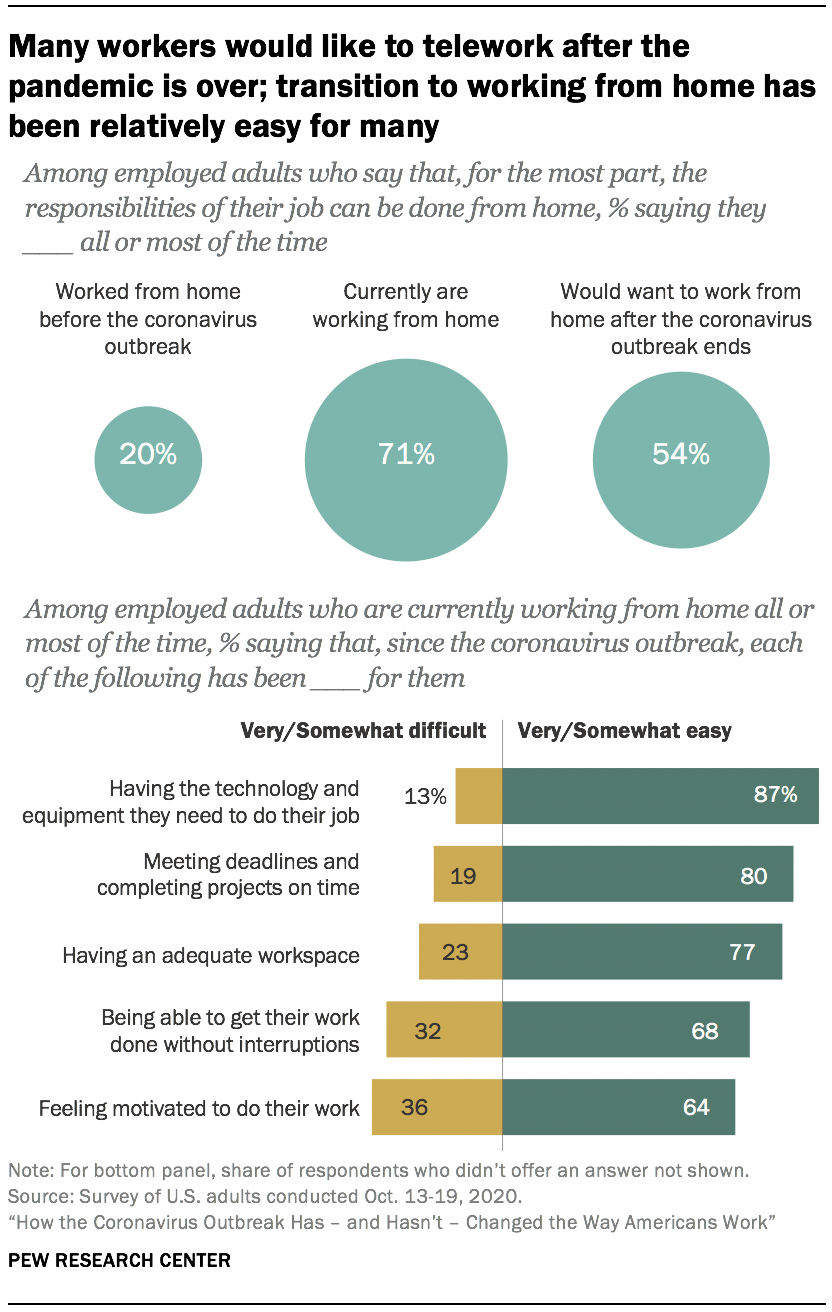

The abrupt closure of many offices and workplaces this past spring ushered in a new era of remote work for millions of employed Americans and may portend a significant shift in the way a large segment of the workforce operates in the future. Most workers who say their job responsibilities can mainly be done from home say that, before the pandemic, they rarely or never teleworked. Only one-in-five say they worked from home all or most of the time. Now, 71% of those workers are doing their job from home all or most of the time. And more than half say, given a choice, they would want to keep working from home even after the pandemic, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

While not seamless, the transition to telework has been relatively easy for many employed adults.1 Among those who are currently working from home all or most of the time, about three-quarters or more say it has been easy to have the technology and equipment they need to do their job and to have an adequate workspace. Most also say it’s been easy for them to meet deadlines and complete projects on time, get their work done without interruptions, and feel motivated to do their work.

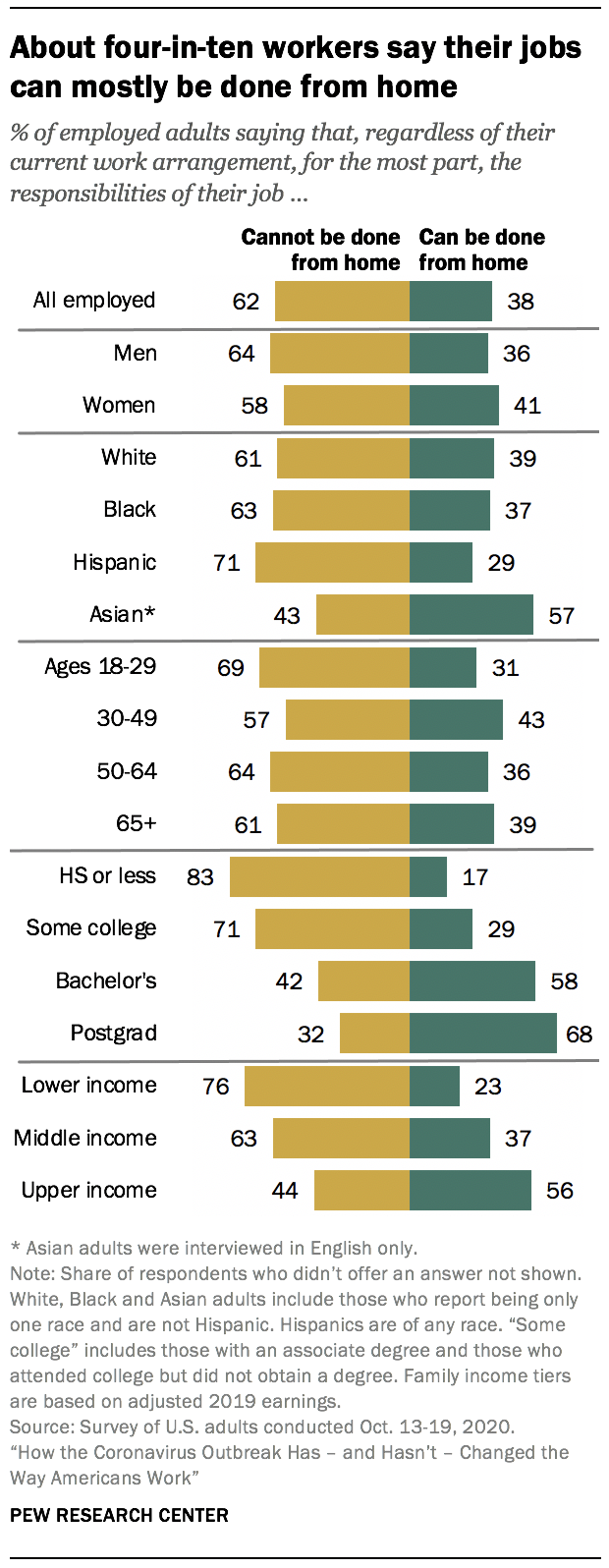

To be sure, not all employed adults have the option of working from home, even during a pandemic. In fact, a majority of workers say their job responsibilities cannot be done from home. There’s a clear class divide between workers who can and cannot telework. Fully 62% of workers with a bachelor’s degree or more education say their work can be done from home. This compares with only 23% of those without a four-year college degree. Similarly, while a majority of upper-income workers can do their work from home, most lower- and middle-income workers cannot.2

Among those who are not currently teleworking all of the time, roughly eight-in-ten say they have at least some in-person interaction with other people at their workplace, with 52% saying they interact with others a lot. At least half of these workers say they’re concerned about being exposed to the coronavirus from the people they interact with at work or unknowingly exposing others. Even so, these workers are largely satisfied with the steps that have been taken at their workplace to protect them from exposure to the virus.

While the coronavirus has changed the way many workers do their job – whether in person or from home – it hasn’t significantly reshaped the culture of work for a majority of employed adults.

Among workers who are in the same job as they were before the coronavirus outbreak started, more than six-in-ten say they are as satisfied with their job now as they were before the pandemic and that there’s been no change in their productivity or job security. Even higher shares say they are just as likely now to know what their supervisor expects of them as they were before and that they have the same opportunities for advancement.

For workers who are working from home all or most of the time now but rarely or never did before the pandemic (and are in the same job they had pre-pandemic), there have been some clear upsides associated with the shift to telework. About half (49%) say they now have more flexibility to choose when they put in their hours. This is substantially higher than the share for teleworkers who were working from home all or most of the time before the pandemic, only 14% of whom say they have more flexibility now. In addition, 38% of new teleworkers say it’s easier now to balance work with family responsibilities (vs. 10% of teleworkers who worked from home before the coronavirus outbreak). On the downside, 65% of workers who are now teleworking all or most of the time but rarely or never did before the pandemic say they feel less connected to their coworkers now. Among more seasoned teleworkers, only 27% feel this way.

The nationally representative survey of 10,332 U.S. adults (including 5,858 employed adults who have only one job or have multiple jobs but consider one to be their primary) was conducted Oct. 13-19, 2020, using the Center’s American Trends Panel.3 Among the other key findings:

A majority (64%) of those who are currently working from home all or most of the time say their workplace is currently closed or unavailable to them; 36% say they are choosing not to go to their workplace.4 When asked how they would feel about returning to their workplace if it were to reopen in the month following the survey, 64% say they would feel uncomfortable returning, with 31% saying they would feel very uncomfortable. For those who are choosing to work from home even though their workplace is available to them, majorities cite a preference for working from home (60%) and concern over being exposed to the coronavirus (57%) as major reasons for this.

Younger teleworkers are more likely to say they’ve had a hard time feeling motivated to do their work since the coronavirus outbreak started. Most adults who are teleworking all or most of the time say it has been at least somewhat easy for them to feel motivated to do their work since the pandemic started. But there’s a distinct age gap: 42% of workers ages 18 to 49 say this has been difficult for them compared with only 20% of workers 50 and older. The youngest workers are among the most likely to say a lack of motivation has been an impediment for them: 53% of those ages 18 to 29 say it’s been difficult for them to feel motivated to do their work.

Parents who are teleworking are having a harder time getting their work done without interruptions.Half of parents with children younger than 18 who are working at home all or most of the time say it’s been difficult for them to be able to get their work done without interruptions since the coronavirus outbreak started. In contrast, only 20% of teleworkers who don’t have children under 18 say the same. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say this has been difficult for them.

Teleworkers are relying heavily on video conferencing services to keep in touch with co-workers, and there’s no evidence of widespread “Zoom fatigue.” Some 81% of employed adults who are working from home all or most of the time say they use video calling or online conferencing services like Zoom or Webex at least some of the time (59% use these often). And 57% use instant messaging platforms such as Slack or Google Chat (43% use these often). Among those who use video conferencing services often, 63% say they are fine with the amount of time they spend on video calls; 37% say they are worn out by it. In general, teleworkers view video conferencing and instant messaging platforms as a good substitute for in-person contact – 65% feel this way, while 35% say they are not a good substitute.

Employed adults with higher educational attainment and incomes are most likely to say their work can be done from home

About four-in-ten U.S. adults who are employed full time or part time (38%) say that, for the most part, the responsibilities of their job can be done from home; 62% say their job cannot be done from home. Workers with higher levels of income and educational attainment are the most likely to say the responsibilities of their job can be done from home.

About seven-in-ten employed adults with a postgraduate degree (68%) and 58% of those with a bachelor’s degree say the responsibilities of their job can mostly be done from home. In contrast, 83% of those with a high school diploma or less education and 71% of those with some college say that, for the most part, their job cannot be done from home. And while a majority of upper-income workers (56%) say they can mostly do their job from home, 63% of those with middle incomes and an even larger share of those with lower incomes (76%) say they cannot.

Asian adults are more likely than those from other racial or ethnic groups to say the responsibilities of their job can mostly be done from home: 57% of Asian American workers say this, compared with 39% of White workers, 37% of Black workers and 29% of Hispanic workers. Women (41%) are more likely than men (36%) to say they can do their job from home, but majorities of both say this is not the case.

Workers’ ability to do their job from home varies considerably by industry.5 For example, majorities in the information and technology sector (84%); banking, finance, accounting, real estate or insurance (84%); education (59%); and professional, scientific and technical services (59%) say their job can mostly be done from home. Among those in government, public administration or the military, 46% say their job can be done from home and 54% say it cannot.

In turn, about three-quarters or more of those employed in retail, trade, or transportation (84%); manufacturing, mining, construction, agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting (78%); and hospitality, service, arts, entertainment and recreation (77%) say that, for the most part, the responsibilities of their job can’t be done from home. Two-thirds of those in the health care and social assistance sector say the same.

About seven-in-ten workers who say their jobs can mostly be done from home say they are teleworking all or most of the time

Amid the coronavirus outbreak, a majority of employed adults who say that the responsibilities of their job can be mostly done from home (55%) say they are currently working from home all of the time. Another 16% say they are doing so most of the time, while 12% say they are teleworking some of the time and 17% are rarely or never working from home.

This marks a significant shift for most of these workers, a majority of whom (62%) say that they rarely or never worked from home before the start of the coronavirus outbreak. Just one-in-five say they worked from home all (12%) or most (7%) of the time before the coronavirus outbreak, while 18% worked from home some of the time.

Across demographic groups, most who say their job can be done from home say they are currently teleworking all or most of the time.

Still, those with higher levels of educational attainment and upper incomes are the most likely to say they are working from home all of the time. About six-in-ten workers with a bachelor’s degree or more education who say they are able to do their job from home (58%) say they are working from home all of the time, compared with 51% of those with less education. And while most of those with upper incomes (65%) say they are currently working from home all of the time, 52% of those with middle incomes and 46% of those with lower incomes say the same.

Most employed adults who have a workplace and who are teleworking all or most of the time say their workplace isn’t available to them

Some 18% of employed adults who are currently teleworking all or most of the time say they don’t have a workplace outside of their home (half of this group is self-employed). Among those who do have a workplace, 64% say they are working from home because their workplace is currently closed or unavailable to them, while 36% say they choose not to work from their workplace.

Asked how they would feel about working at their workplace if it were to reopen in the month following the survey, 64% of those whose workplace is currently closed or unavailable to them say they would feel uncomfortable, with 31% saying they would feel very uncomfortable. Some 36% say they would feel at least somewhat comfortable working at their workplace if it were to reopen in the month following the survey. There are no significant differences across demographic groups.

Among teleworkers who are choosing not to work from their workplace, majorities say a preference for working from home (60%) and concerns about being exposed to the coronavirus (57%) are major reasons why they are currently working from home all or most of the time. Smaller shares cite restrictions on when they can have access to their workplace (14%) or relocation (either permanent or temporary) to an area away from where they work (9%) as major reasons why they are currently working from home.

About two-thirds of parents with children younger than 18 who are working from home all or most of the time and whose workplace is open (65%) point to child care responsibilities as a reason why they’re working from home; 45% say this is a major reason.

The shift to remote work has been easy for many workers; younger workers and parents more likely to have faced challenges

Overall, a majority (56%) of adults who are working from home all or most of the time say, since the coronavirus outbreak started, it has been very easy for them to have the technology and equipment they need to do their job. An additional 30% say this has been somewhat easy for them.

Those who worked from home before the coronavirus outbreak may have an advantage in this regard. About two-thirds (64%) of workers who worked from home at least some of the time before the pandemic and are doing so all or most of the time now say it’s been very easy for them to have the technology and equipment they need to do their job. This compares with 50% of current teleworkers who rarely or never worked from home prior to the outbreak.

Having an adequate workspace at home has also been easy for most teleworkers – 47% of those who are now working from home all or most of the time say this has been very easy, and 31% say it’s been somewhat easy. Here again, those who worked from home prior to the pandemic may have an edge over those who are newer to teleworking. While roughly half (51%) of those who worked from home at least some of the time before the coronavirus outbreak say it’s been very easy for them to have an adequate workspace, a smaller share (42%) of those who didn’t work from home prior to the outbreak say the same.

When it comes to their ability to meet deadlines and complete projects on time, most teleworkers say this has been easy for them, with 43% saying this has been very easy and 37% saying it’s been somewhat easy.

Those working from home are finding it somewhat less easy to get their work done without interruptions and to feel motivated to do their work. While a majority say it has been very or somewhat easy for them to be able to get their work done without interruptions, roughly a third say this has been somewhat (24%) or very (8%) difficult.

Similarly, while more than six-in-ten teleworkers say it has been very or somewhat easy for them to feel motivated to do their work, more than three-in-ten say this has been difficult for them (29% somewhat difficult, 7% very difficult).

Barriers to productivity vary by age, parental status

There is a significant age gap in the extent to which workers are facing challenges in their virtual work lives. Among those working from home all or most of the time, those younger than 50 are significantly more likely than older workers to say it’s been difficult for them to be able to get their work done without interruptions (38% for workers ages 18 to 49 vs. 18% for workers 50 and older) and feel motivated to do their work (42% vs. 20%). The youngest workers are among those most likely to say a lack of motivation has been an impediment for them: 53% of those ages 18 to 29 say it’s been difficult for them to feel motivated since the pandemic began.

The age gap is less pronounced but still significant when it comes to having an adequate workspace and meeting deadlines and completing projects on time. In each case, workers younger than 50 are more likely than their older counterparts to say this has been difficult for them. These age gaps persist after controlling for parental status. Even among adults who do not have children, those younger than 50 are facing more difficulty in some aspects of their work.

With widespread school and daycare closures, many working parents have their children at home as they’ve transitioned to remote work. Half of teleworking parents with children younger than 18 say, since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, it’s been difficult for them to be able to get their work done without interruptions.6 A far smaller share of those who do not have minor children (20%) say the same. This difference persists across genders, with both mothers and fathers more likely than their counterparts without children to say this has been difficult for them. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say this has been difficult for them.

Among teleworkers, parents are somewhat more likely than adults without minor children to say it’s been difficult for them to have an adequate workspace – 28% vs. 19%. In addition, parents are more likely than non-parents to say it’s been difficult for them to meet deadlines and complete projects on time while working at home. Similarly, parents are somewhat more likely than non-parents to say it’s been difficult for them to have the technology and equipment they need to do their job.

Teleworkers are taking advantage of online tools and platforms to keep in touch with co-workers, and most see them as a good substitute

For many who are working from home, online communication tools have become a vital part of the workday. Roughly eight-in-ten adults who are working from home all or most of the time (81%) say they use video calling or online conferencing services like Zoom or WebEx to keep in touch with co-workers, with 59% saying they often use these types of services. Some 57% say they use instant messaging platforms such as Slack or Google Chat at least sometimes (43% use these often).

While large majorities of workers across age groups say they use video calling or online conferencing at least some of the time, workers ages 65 and older are the least likely to say they do this often.

There’s a significant socioeconomic divide in the use of these types of services. Among four-year college graduates who are working from home all or most of the time, 64% say they often use video calling or online conferencing. In contrast, 48% of teleworkers without a four-year college degree say they do this often. Similarly, 69% of upper-income workers often use these types of services, compared with 56% of middle-income workers and 41% of lower-income workers.

Workers who play a supervisory role in their organization (70%) are more likely than those who don’t (55%) to say they often use video calling or online conferencing. Across industries, those working in education and information technology are among the most likely to say they often use video conferencing.

When it comes to instant messaging platforms such as Slack or Google Chat, usage patterns are somewhat different. Again, age matters: 49% of teleworkers younger than 50 say they use these types of platforms often compared with 30% of those 50 and older. But there is no gap along educational lines, and the income gap is more modest. Workers who are employed in the information technology industry are more likely than those in most other industries to rely on these platforms.

Among all who are working from home, those who do so all of the time (47%) are much more likely than those who work from home most of the time (28%) to say they use these platforms often.

Most see online tools as a good substitute for in-person contact

Most teleworkers (65%) who at least sometimes use remote technologies such as video conferencing or instant messaging say these online tools are a good substitute for in-person contact, while 35% say they are not a good substitute. Views on this differ by gender, with women (70%) more likely than men (60%) to view these tools as a good substitute. There is also a difference by education: 70% of teleworkers without a bachelor’s degree see these online tools as a good substitute for in-person contact, compared with 62% of those with a four-year college degree.

While these technologies have helped companies and organizations operate effectively during the pandemic, there has been widespread concern that video calls in particular are taking a toll on workers. Among teleworkers who say they use video calling or online conferencing services often, most (63%) say they are fine with the amount of time they spend on these platforms; 37% say they are worn out by it.

Younger teleworkers (ages 18 to 49) who use these platforms often are more likely than their older counterparts to say they feel worn out by the amount of time they spend on video calls (40% vs. 31%). Feeling worn out is also more prevalent among those with a bachelor’s degree or higher (41%) than among those with less education (27%). In addition, supervisors who use these platforms often are more likely than those who don’t supervise others (but also use video platforms often) to say they feel worn out by the amount of time they spend on these types of calls (47% vs. 33%).

Looking ahead, a majority of those who say their job can be done from home say they’d like to telework all or most of the time post-pandemic

More than half of employed adults who say that their job responsibilities can mostly be done from home (54%) say that, if they had a choice, they’d want to work from home all or most of the time when the coronavirus outbreak is over. A third say they’d want to work from home some of the time, while just 11% say they’d want to do this rarely or never. Some 46% of those who rarely or never teleworked before the coronavirus outbreak say they’d want to work from home all or most of the time when the pandemic is over.

Men and women who can do their work from home are about equally likely to say they’d want to work from home all or most of the time after the pandemic, but women are more likely than men to say they’d want to work from home all of the time (31% vs. 23%). This is the case whether they have minor children or not. In fact, the shares of workers with and without children younger than 18 who say they would want to work from home all of the time when the outbreak is over are nearly identical.

Similar shares across age, income and racial and ethnic groups say they’d want to work from home all or most of the time after the coronavirus outbreak is over if they had a choice. Among employed adults with some college or less education who say they can do their job from home, 60% say they would want to work from home all or most of the time post-pandemic, compared with half of those with at least a bachelor’s degree.

For those workers who are spending time at their workplace and interacting with others, at least half are concerned about being exposed to – or spreading – the coronavirus

Most employed adults don’t have the option of working from home, and some of those who do are still spending some time in the office or at their workplace. For many of these workers, the pandemic has brought a new concern about their health. Among those who are not working exclusively from home and who have at least some in-person interactions with other people at their workplace, a majority say they are at least somewhat concerned about being exposed to the coronavirus at work (21% say they are very concerned). About half are concerned that they might unknowingly spread the virus to the people they interact with at work (19% are very concerned).

Women (60%) are more likely than men (48%), and workers younger than 50 (56%) are more likely than older workers (50%), to be at least somewhat concerned about being exposed to the virus. And Black (70%) and Hispanic (67%) workers are more concerned about this than White workers (48%). These patterns are similar when it comes to potentially passing the virus along to others at work. In addition, lower-income workers (61%) express a higher level of concern than those with upper incomes (48%) about being exposed to the virus (similar shares across income groups are concerned about spreading the virus to others).

Most workers are satisfied with the steps that have been taken in their workplace to keep them safe from COVID-19

Among those who either cannot do their work from home or can but are not working from home all of the time, about eight-in-ten say they are very (39%) or somewhat (42%) satisfied with the measures that have been put in place to protect them from being exposed to the coronavirus. About one-in-five say they are not too (13%) or not at all (6%) satisfied.

White workers who are spending some time at their workplace are more satisfied than Black or Hispanic workers with the steps that have been taken to ensure their safety: 45% of White workers, compared with 31% of Black and 29% of Hispanic workers, say they are very satisfied. Workers ages 50 and older are also more likely than their younger counterparts to be very satisfied (50% vs. 34%). There is an income gap as well: Lower-income workers (33%) are significantly less likely than middle-income (39%) and upper-income (49%) workers to say they are very satisfied with the measures put in place where they work.

About a quarter of workers say they are less satisfied with their job than they were before the coronavirus outbreak

While the coronavirus outbreak has changed how Americans work in some ways, from increased telework to health concerns among those who can’t or choose not to work from home, majorities of workers say they have seen little change in various aspects of their work lives compared with before the outbreak. For example, about three-quarters of those who are in the same job as before the outbreak started say they have about the same opportunities for advancement (76%) and that there has been no change in how easy or hard it is to know what their supervisor expects of them (77%). About seven-in-ten say they have about as much job security (70%) and flexibility to choose when they put in their hours (68%) as they did pre-pandemic.7 Still, some workers have noted a change in the way things are going for them at work.

Overall, about a quarter (23%) of workers who are in the same job say they are less satisfied with their job compared with before the coronavirus outbreak, while 13% say they are now more satisfied. When asked about specific aspects of their job, a third say they feel less connected to their co-workers, 26% say it’s harder for them to balance their work and family responsibilities, about one-in-five say they have less job security and fewer opportunities for advancement (19% each), and 16% say it’s harder to know what their supervisor expects of them. On each of these, smaller shares note an improvement in the way things are going compared with before the coronavirus outbreak. In turn, a higher share say they now have more flexibility to choose when they put in their hours (19%) than say they have less flexibility (13%).

Assessments of how some elements of work life have changed compared with before the coronavirus outbreak vary by work arrangements. Among employed adults who have not changed jobs since the pandemic began, four-in-ten of those who are working from home all or most of the time say they have more flexibility to choose when they put in their work hours than they did before the coronavirus outbreak. That compares with 21% of those who can do their job from home but are doing so only some of the time, rarely, or never, and an even smaller share (9%) of those whose work can’t be done from home who say they have more flexibility. Workers who are working from home all or most of the time are also more likely than other workers to say that it’s now easier for them to balance work and family responsibilities and that they are more satisfied with their job than before the coronavirus outbreak.

At the same time, workers who haven’t changed jobs and are working from home all or most of the time (57%) are more likely to say they feel less connected to their coworkers than those who can do their job from home but are doing so less often or not at all (40%) and those whose job can’t be done from home (21%). They are also more likely to say they have fewer opportunities for advancement than they did before: 23% of those who are working from home all or most of the time say this, compared with 18% of those who can do their job from home but are not doing so all or most of the time and 17% of those who can’t do their job from home.

When it comes to the number of hours workers are putting in, a third of those who are working from home all or most of the time say they are working more hours than they did before the coronavirus outbreak. Smaller shares of those who can do their job from home but aren’t doing so all or most of the time (23%), and those who can’t do their job from home (21%), say they’re working more hours. Workers whose job can’t be done from home are the most likely to say they are now working fewer hours (20% vs. 13% of those who can do their job from home but are doing so some of the time or less often and 14% of those who are working from home all or most of the time).

These assessments also vary to some extent across demographic groups, largely mirroring demographic divides in work arrangements. For example, those in upper-income families and those with a bachelor’s degree or more education – groups that are among the most likely to be working from home all or most of the time – are more likely than those with middle or lower incomes and those without a bachelor’s degree to say they have more flexibility to choose their hours and that they feel less connected to their co-workers.

Still, even when accounting for the fact that work arrangements vary widely across demographic groups, some differences remain. Among workers who are in the same job as before the pandemic and who are currently working from home all or most of the time, those with at least a bachelor’s degree are more likely than those with some college or less education to say they now have more flexibility to choose when they put in their hours (46% vs. 28%, respectively) and that they feel less connected to their co-workers (62% vs. 45%). And these differences also persist when looking at workers with and without a bachelor’s degree who say that, for the most part, the responsibilities of their job can’t be done from home.

Among working parents with children younger than 18 who are in the same job as before the coronavirus outbreak started, a third say it’s now harder for them to balance work and family responsibilities; 22% of those who do not have minor children say the same. Mothers (39%) are more likely than fathers (28%) to say it’s harder for them to balance work and family responsibilities compared with before the coronavirus outbreak.