New Zealand Will Ban Most Single-Use Plastics by 2025

The country also announced the launch of a fund to find alternatives to plastic.

Plastic cutlery that cannot be recycled ends up contributing to plastic pollution of the environment. | Image: Flickr/Raban Holzner

Why Global Citizens Should Care

Plastics are used widely around the world, but they pose incredible harm to the environment and wildlife. Over half of the plastic produced today is designed to be single-use and thrown away, polluting waterways and contributing to climate change. More governments are banning the use of single-use plastics than ever before, but more must be done to protect the environment. Join us by taking action here to defend the planet.

New Zealand has just announced that it will phase out single-use plastics between 2022 and 2025 in an effort to promote environmental sustainability.

The country will ban plastic drink stirrers, straws, and cutlery, according to the Guardian, as well as PVC and polystyrene food and drink packaging.

What to Know

Over 300 million tonnes of plastics are produced each year, half of which are single-use.

Reducing your plastics footprint helps protect our oceans, people and the planet.

Help reduce single-use plastics — sign the pledge today.

Despite New Zealand’s reputation as one of the greenest countries in the world, it has had trouble managing waste, leading to challenges in the fight against climate change. Last year, a government report found that nearly 60% of the country’s rivers were polluted above acceptable levels.

While New Zealand had already banned plastic bags from being used in 2019, this year’s initiative will expand the ban of single-use plastics to target items that commonly end up in landfills and pollute soil, waterways, and the ocean. The government also announced a $50 million pledge to the Plastics Innovation Fund, which will launch in November to help businesses find alternatives to plastic packaging.

“We estimate this new policy will remove more than 2 billion single-use plastic items from our landfills or environment each year,” David Parker, New Zealand’s environment minister, said. “Phasing out unnecessary and problematic plastics will help reduce waste to landfill, improve our recycling system, and encourage reusable or environmentally responsible alternatives.”

Currently, the world produces almost 300 million tonnes of plastic waste every year. Half of all plastic that is produced is designed to be used only once, including plastic water bottles, bags, and cutlery. These items take anywhere from 20 to 500 years to decompose, harming wildlife and polluting the environment along the way.

New Zealand is joining a spate of other countries that have taken steps to prevent plastic from contributing to environmental degradation. Last year, England announced a ban on plastic straws, drink stirrers, and cotton buds to curb use of some single-use plastics. Two Australian states — New South Wales and Western Australia — recently announced initiatives to end reliance on plastic and ban harmful items by the end of 2022.

While many environmentalists and businesses are applauding the country’s efforts to reduce use of plastic, some point out that more can — and should — be done before New Zealand can correct its waste problem.

The EU’s new directive on single-use plastics could stifle innovation

There has been plenty of discussion about how legislation – or lack thereof – can hinder the emergence and widespread use of solutions that can solve some of the most difficult challenges of our times. With enough resources, technology and innovation can be developed fast, but legislation often falls behind and it can take years for lawmakers to catch up.

By this July 3, the member states of the EU should have implemented the new Directive on Single-Use Plastics that bans nine plastic products, such as single-use straws and cutlery, often found littering the beaches of Europe. The aim is certainly noble: to prevent and reduce the impact of these plastic products on the environment and on human health.

The directive is also meant to serve as a step towards a circular economy with innovative and sustainable business models, products and materials – all geared towards more efficient use of our planet’s limited resources, so that we can protect and maintain our world for future generations.

Sadly, due to the way the Directive defines plastics, it can prove to be a difficult obstacle to innovative, sustainable solutions aimed at saving the world from plastic waste.

The directive defines all synthetic polymers (e.g. fossil-based polymers) and all chemically modified natural polymers as plastics, so that this definition now also includes bio-based biodegradable and compostable plastics products – even though many of those products could help us fight plastic pollution by offering effective solutions.

In fact, the definition in the law is so broad that it technically includes materials that can be even found in fried eggs as during heating egg’s polymers are chemically modified. They can also be found in many kinds of ketchup and ice creams as they contain a food additive called carboxymethyl cellulose.

All products containing these polymers (even tiny amounts) fall in the scope of the directive and no minimum threshold is given. And yet these materials are safe for people and the environment, and they leave no permanent microplastics behind.

Everyone knows we need to tackle the plastic crisis. According to World Economic Forum, the production of plastics has exploded over five decades from 15 million tons in 1964 to 311 million tons in 2014, and the amount is expected to double by 2050.

Meanwhile, according to Material Economics, it was reported in 2018 that the EU’s recycling rate for plastics packaging is 40%, but, according to research, the effective recycling rate is just 10–15%.

While plastic waste has been a great concern for decades and measures have been taken to make recycling easier, there’s also another threat. Microplastics have emerged as a significant issue during the last 10 years or so. As plastic products break down, they release microplastics – small plastic particles of less than 5mm in at least one dimension – that end up in nature, eventually accumulating in animal and human bodies. In fact, they release plastic particles already in use; for instance, when people open plastic containers.

According to an analysis commissioned by WWF, we could be ingesting around 5 grams of plastic every week. Microplastics have become so prevalent that plastic particles are being carried by the wind – and once they’re airborne, little can be done to stop them. They are officially part of the air we breathe.

We’ve all seen the pictures and news of whales and birds washing up on beaches, their stomachs filled with plastic items, such as bags and different kinds of packaging. Microplastic waste is more difficult to visualize, but we know from research that microplastics have already permeated our world. At the moment, very little research exists on their long-term impacts.

Meanwhile, the EU’s new directive does not even address the critical issue of microplastics. Banning synthetic polymers and chemically modified natural polymers does nothing to curb the spread of microplastics into nature, and animal and human bodies.

I’m concerned that due to the broad definition of plastics, the directive will not effectively meet its objectives to promote new sustainable material innovations. The broad definition of plastics may steer future policies in the wrong direction and close the door on effective and proven ways of tackling plastic pollution. The problem will repeat itself if the wide definition for plastics in the directive is adopted to other new regulations.

In fact, the same problems described here in relation to the new law can also be seen in connection with the review process of the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD) within the EU. Unless the individual member states do not step up and fight for these sustainable materials offering immediate help in fighting plastic pollution, we might face a similar calamity in connection with the PPWD as we have now with the latest directive on single-use plastics.

I’m not alone with these concerns. According to FinnCERES, a Finnish competence center focusing on the area of materials bioeconomy, the definition of plastic in the directive on single-use plastics means that we are at risk of losing the possibility of using bio-based materials for packaging and textiles and closing doors for innovation that could contribute to solving the most pressing environmental issues of our times.

At the moment, a reform of Extended Producer Responsibility is under development in several EU countries. Many member states are considering introducing specific plastic packaging taxes.

In addition, I am worried that there will be an increasing amount of legislation that does not recognize plant-based materials that do not leave permanent microplastics behind, but groups them together with traditional plastics. This would not only limit innovation, but also slow down the fight against plastic pollution.

Let us hope that this definition of plastics is only a temporary setback. I would like to see a new category for materials that do not leave permanent microplastics behind. However, the planned revision of the EU’s directive on single-use plastics in 2027 is too late. Six years is a long time to be held back. Nature and innovative solutions need support today.

EU bans 10 most common single-use plastic items found on beaches

As of this week, straws, plastic bottles, coffee cups and takeaway containers made from certain materials are banned in the EU. Items made from expanded polystyrene, specifically, are no longer allowed to be sold.

The exact items included are 10 single-use plastics that are most commonly found thrown away on beaches.

Expanded polystyrene is being targeted because it easily breaks down into tiny white plastic balls which are blown around by the wind and eaten by fish or birds who think it’s food.

The new law, called the Single-Use Plastics (SUP) Directive, requires all 27 EU member states to enforce the new guidelines. Norway, despite not being a member of the EU, is also implementing the SUP directive as a member of the European Economic Area.

The laws state that the aim is to prevent and reduce the impact of certain plastic products on the environment, in particular the aquatic environment, and on human health, as well as to promote the transition to a circular economy with innovative and sustainable business models, products and materials.

The directive will be transposed into national law and applied as of 3 July 2021 - any countries who don't respect these obligations will be fined.

How were the new laws decided?

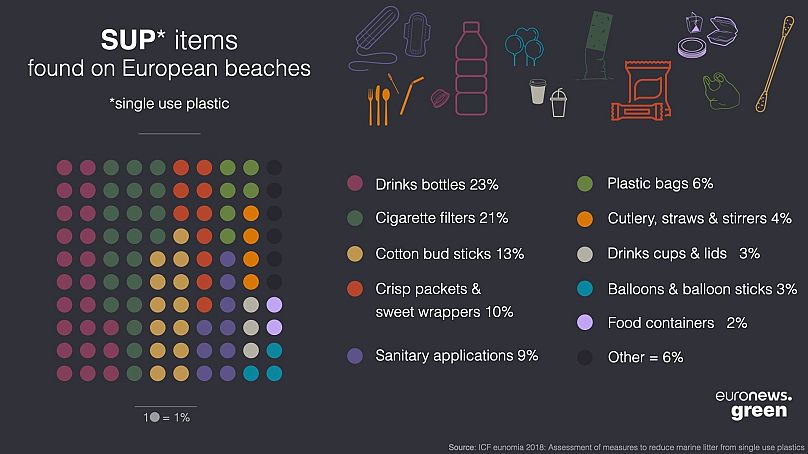

Single-use plastics (SUPs) make up 50 per cent of all litter found on European beaches. To plan the directive, the European Commission commissioned a study that used litter data from research projects, monitoring programmes and clean-ups on 276 European beaches in 17 EU countries. It found that half of all litter on these beaches in 2016 derived from SUP items.

The EU study also reported that around 90 per cent of all single-use plastics found on European beaches consist of just 10 different types of items. As a result, the EU decided to target these specific items in its SUP directive.

It bans the top 10 SUP items for which there is an accessible innovative alternative, no matter whether it is a reusable product or a single-use product made of another material other than plastic.

Infographic showing how many SUP items are found on European beachesSelina Oberpriller

What makes an item single-use?

Single-use plastics (SUPs) are produced to be used once, from a few seconds to a few minutes. SUPs include items like food wrappers, take-away containers, coffee cups and plastic bottles. Because they are used for such a short time, SUPs are more likely to be littered.

SUPs include items like food wrappers, take-away containers, coffee cups and plastic bottles.

“When we are on the go and we only need them for a few minutes, we often don't know what to do with those plastics,” says Gaëlle Haut, project manager for EU affairs at Rethink Plastic, an alliance of European NGOs fighting plastic pollution.

What about bioplastics?

For other SUPs the EU did not consider environmentally-friendly alternatives advanced enough for a market restriction. Hence, not all single-use plastic cups, food and beverage containers will be banned, just those made of expanded polystyrene.

Rethink Plastic believes that enough alternatives are available to ban all kinds of SUP food and beverage containers.

Interestingly enough - bioplastics are being banned, despite some members of the industry trying to have them exempted. Unlike conventional plastics, bio-based plastics are made of biological resources instead of fossil fuels like coal, gas or oil. Yet according to Haut, those bioplastics are “just as bad as conventional plastics.”

Their decomposition takes a very long time during which the plastics impact marine life and, “they only decompose under very specific conditions which are not even found in nature, let alone in the ocean.”

The items in the top 10 items not covered by the ban

For the top 10 SUP items for which alternatives are not as developed yet, the directive makes other requirements. To make consumers more aware of which products contain plastics and how to dispose of them correctly, period products, wet wipes, tobacco products and cups will need to have warning labels.

One of these is what Haut calls “a plague”, cigarette butts.

Every year, butts are the item most commonly found in beach cleans organised by Haut’s NGO Surfrider Foundation Europe. In the study the EU directive was based on, cigarette butts are the second most found SUP item.

Most cigarette filters include plastics and even though some plant-based alternatives exist, the EU calls for further innovation towards sustainable options.

Period products, wet wipes, tobacco products and cups will need to have warning labels.

Instead of banning them, the directive forces tobacco producers to help with the problem.

The measure is called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), and means producers will have to cover the costs for litter clean-up. This also applies to wet wipes and balloons.

However, only the market ban and the labeling requirements enter into force on 3 July. EPR and all the other measures addressing the items regarded as not fully replaceable yet will come within the next few years.

Rethink Plastic is demanding tighter deadlines.

Warning labels must be added to certain plastic items in futureSelina Oberpriller

“There is no reason why citizens should already take responsibility for plastic pollution [now] and some industry players are guaranteed some more years,” says Haut.

The public approval towards the directive is expected to be high. In the 2017 Eurobarometer, which consists of around 1000 interviews per Member State, the vast majority of respondents said it was important that products should be designed in a way that plastic can be recycled (94 per cent approval).

They also said the industry should make an effort to reduce plastic packaging (94 per cent), the public should be educated on how to reduce plastic waste (89 per cent) and local authorities should provide more and better collection facilities for plastic waste (90 per cent).

Will all Member States meet the deadline of July 3rd?

The Member States have had two years to implement the measures of the directive in national law. Some have already done so early, for example France banned the first SUP items in the beginning of 2020. But not all countries have submitted a law draft to the Commission.

Rethink Plastic assessed how the Member States are doing in implementing the EU directive into national law. They found that four countries have not implemented the ban: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania. Many others have picked and chosen some of the measures, rather than going full hog.

While Haut says the directive is a big step in the right direction, she also thinks many more steps could be made and Rethink Plastics calls on all countries to be more ambitious than what the directive says.

Despite the ban, current SUPs in stock will still be up for sale in Europe to avoid masses of items being discarded without ever having been in use.