Bumble closes to give 'burnt-out' staff a week's break

Bumble, the dating app where women are in charge of making the first move, has temporarily closed all of its offices this week to combat workplace stress.

Its 700 staff worldwide have been told to switch off and focus on themselves.

One senior executive revealed on Twitter that founder Whitney Wolfe Herd had made the move "having correctly intuited our collective burnout".

Bumble has had a busier year than most firms, with a stock market debut, and rapid growth in user numbers.

The company announced in April "that all Bumble employees will have a paid, fully offline one-week vacation in June".

A spokeswoman for Bumble said a few customer support staff will be working in case any of the app's users experience issues. These employees will then be given time off to make sure they take a whole week of leave.

The spokeswoman confirmed that the majority of Bumble's staff are taking the week off.

Bumble has grown in popularity during lockdown as boredom set in and swiping to find a match picked up.

The number of paid users across Bumble and Badoo, which Bumble also owns, spiked by 30% in the three months to 31 March, compared with the same period last year, according to its most recent set of results.

Ms Wolfe Herd also became the youngest woman, at 31, to take a company public in the US when she oversaw Bumble's stock market debut in February.

She rang the Nasdaq bell with her 18-month-old baby son on her hip and in her speech she said she wanted to make the internet "a kinder, more accountable place".

Bumble's unique HQ

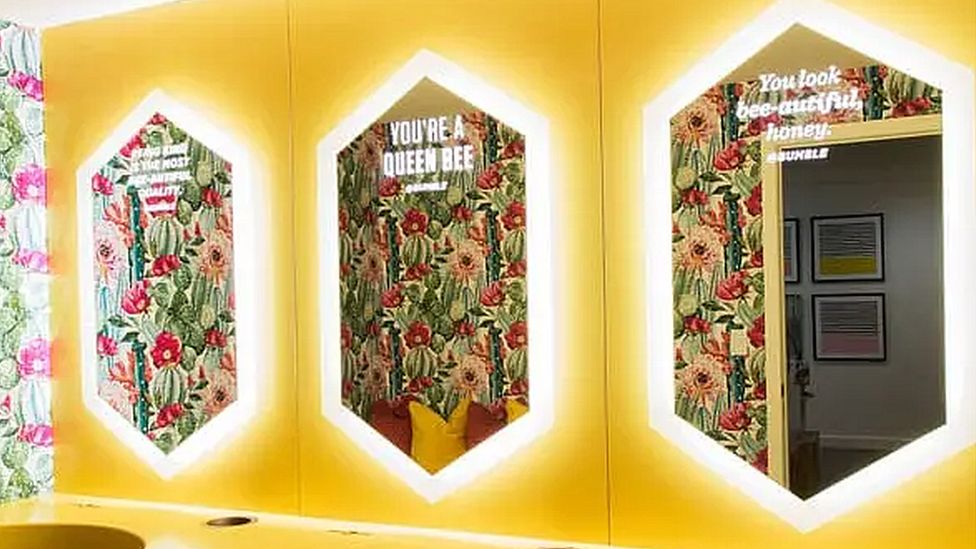

image copyrightLaura Alexander/Bumbleimage captionIn your face: Bumble's head office is all about positivity

Bumble founder Whitney Wolfe Herd's quest to make the internet a "kinder" place extends to the company's head office. And then some.

Back in 2017, the firm unveiled its new headquarters in Texas. Saturated in Bumble's signature yellow, wall mirrors are emblazoned with messages such as "you look bee-autiful honey". Even the light switches have slogans, telling people to "shine bright like a diamond".

It also boasts a "Mommy Bar" - described as a "private lactation space" by Ms Wolfe Herd - as well as fortnightly manicures, hair trims and "blowouts" which the founder said showed "appreciation for our busy bees".

Working hours? Not nine to five apparently. Employees can choose the hours they want, just as long as the work gets done.

Could the UK see the same sort of office environment here? With many people spending so much time at home recently, perhaps companies will follow through on making changes to working life. Just don't hold out for free manicures though.

Workers in other industries have complained about working long hours and the effect on their well-being.

Earlier this year, a group of younger bankers at Goldman Sachs warned they would be forced to quit unless conditions improved. They said they were working an average of 95 hours a week and slept five hours a night.

A spokeswoman for the investment bank said at the time: "A year into Covid, people are understandably quite stretched, and that's why we are listening to their concerns and taking multiple steps to address them."

Prior to Covid, one of the most high-profile examples of overwork emerged in when Antonio Horta-Osorio, then the relatively new chief executive of Lloyds Banking Group, was forced to take a leave of absence. After joining the bank in January 2011, Mr Horta-Osorio took eight weeks off from November after prolonged insomnia led to exhaustion.

image copyrightGetty Imagesimage captionFormer Lloyds' Banking boss Antonio Horta-Osorio was forced to take time off due to exhaustion

Following his return, Mr Horta-Osorio - now chairman of Credit Suisse - led a re-evaluation at the bank on the importance of mental health.

Wider debate

Bumble made its announcement after several tech companies have unveiled their plans for remote working as the economy reopens.

Twitter has said that it expects a majority of its staff to spend some time working remotely and some time in the office. That's despite its boss Jack Dorsey initially saying that employees could work from home "forever".

And Google rejigged its timetable for bringing people back to the workplace. As of 1 September, employees wishing to work from home for more than 14 days a year would have to apply to do so.

But Apple employees have launched a campaign pushing back against boss Tim Cook's plans for a widespread return to the office, according to media reports earlier in June.

It followed an all-staff memo in which the Apple chief executive said workers should be in the office at least three days a week by September.

Dealing with burnout

The key to coping with burnout is control, according to experts. "Not everyone has the option of leaving their job but it's about doing what you can with the things you can control," says Siobhan Murray, author of 'The Burnout Solution'.

Cary Cooper, president of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development and professor of organisational psychology and health at the University of Manchester, says it is "important that individuals take control of their environment to manage the hours they work and ensure that they're socially connected." He advises:

- Take control

- Don't work consistently long hours, engage in activities unrelated to work

- Connect socially with friends and people you like

- Have some 'me time'

- Avoid unhealthy behaviours and negative coping mechanisms

- Help other people

- Be positive

But companies must play their part too, says Trades Union Congress health and safety officer, Shelly Asquith. Stress is an "occupational hazard" she says and it "requires risk assessment and management to protect the wellbeing of staff".

Other companies, such as accountancy firm KPMG, have introduced new measures to combat the fatigue some workers might feel after more than a year of working in a less-than-ideal home set-up.

Voice-only meetings, for example, are now required on Fridays to reduce the need for video calls.

It is in stark contrast to comments made by KPMG's UK chairman, Bill Michael, in February when he told colleagues to "stop moaning" during a virtual meeting discussing the pandemic and possible cuts to their pay, bonuses and pensions.

According to the Financial Times, Mr Michael also told employees to stop "playing the victim card". Mr Michael has since apologised and resigned.

Should Your Company Provide Mental Health Apps to Employees?

Thanks to the pandemic, there is heightened interest in new effective options for preventing and treating anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric illnesses. Human resources managers are looking for new ways to support their employees. Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions (CDC) suggests that the mental health of younger people and minorities has been especially impacted.

In the last 12 months, our research team at the division of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School, fielded a dramatic increase in questions related to digital mental health, specifically digital mental health apps. Here are three of the most common questions that arose in conversations with physicians, senior executives, and HR managers, and our answers, which are based on our experiences in clinical care, clinical research studies, and industry analysis.

1. Should my company offer access to mental health apps?

The best thing you can do for your employees is to offer them robust health care coverage at a reasonable price. This coverage should include comprehensive mental health care that makes face-to-face therapy with a licensed clinician affordable and accessible. A mental health app on its own is not an equal substitute. That’s because to date, there isn’t evidence that self-help apps are as effective as therapy or medication in treating mental illness. But they may be able to help some people better cope with stress and symptoms related to anxiety or depression.

Consequently, mental health apps should only be used to complement therapy and other forms of self-care, such as exercise, healthy diet, and restful sleep. Like any complementary therapy, apps will not solve the root cause of mental health problems if there are underlying systematic workplace factors related to toxic cultures, abuse, and so on. HR managers should rule out these broader causes before focusing on app options.

Evaluating evidence for the usefulness of an app can be challenging. While we are seeing a rise in published studies and are hopeful evidence that substantiates mental health apps will grow, the science behind the apps that employers offer employees is still limited. Indeed, we have found that the majority of commercially available apps make claims related to mental health that they cannot back up with scientific evidence. Therefore, HR managers must decide — based on their budget, their workforce’s unique set of needs, and often on an individual-by-individual basis — whether the benefits of easy access and lower cost afforded by mental health apps are compelling enough with or without rigorous research that validates their efficacy.

Another consideration is that many mental health apps today are increasingly supported by coaches — as opposed to licensed clinicians — to drive engagement, which should give HR managers pause. HR managers will want to explore who these coaches are and what professional degrees or other accreditations, if any, they hold. Sometimes this information can be obtained by simply browsing a company’s website. If it’s not obvious, managers should reach out to the company directly and ask or consult a mental health professional who understands accreditations and the education they require.

2. What is the best app I can offer my employees to help them manage stress or anxiety?

While apps themselves are unable to treat a mental health condition, they can offer employees access to new tools, skills, and resources that may help them better cope and manage. There are hundreds of apps offering immediate access to mindfulness exercises, mood tracking, mental health education, specific therapy skills, biofeedback, and more. Each can potentially be useful towards reducing stress, negative thoughts, or even cravings related to addictions. But we don’t think there is a single best mental health app for everyone and recommend that HR managers seek apps that can address employees’ specific needs.

We avoid lists of “top 10 apps” because of their subjective ranking and how quickly apps update and even reinvent themselves. We have seen many app rating websites posting reviews of defunct apps and even found that 28% of apps recommended to students by colleges were no longer available for download. A good rule of thumb empirically derived from our team is that if a rating is more than six months old, ignore it and anything else on that list or website.

We also caution against evaluating apps on the basis of the number of times they’ve been downloaded, their star ratings, or advertising. While a handful of apps have emerged as the most popular or well known, these are not always the most effective tools.

HR managers should look deeper and ask tougher questions: What in the workplace may be contributing to stress or anxiety? What does this mean for mental health of employees and what resources do they need to cope? If employees have variable hours, then an app that primes users for sleep might be beneficial, whereas if burnout is a concern, then making conversations with licensed therapists available to employees might be more important.

To help HR managers make sense of the growing number of available apps and find the best match for their employees’ specific needs, our team built and maintains an evidence-based, free, online resource, the M-Health Index and Navigation Database, which is supported by a charitable gift from the Argosy Foundation. The database includes information on more than 400 apps across 105 dimensions, including costs, supported conditions, functionalities, features, evidence, engagement, and privacy.

3. How do I evaluate the economic impact of a digital mental health product?

We know that the burden of mental health is costly, and it is effective to prevent and treating mental illness. Many websites for mental health apps make claims about return on investment and savings that are designed to attract HR managers. But while there aren’t definitive numbers (yet) that indicate the cost-effectiveness of digital mental health tools, we advise HR managers to consider four types of data to estimate potential savings.

First, managers should estimate the cost due to the conditions (e.g., lost productivity) per employee. Second, managers should request engagement data to learn the average percentage of users who will remain active on the app after two weeks. This information is seldom publicly available, but it’s critical: Research suggests that average engagement rates may be as low as 5% after two weeks. Third, managers should ask the company for estimates of the app’s positive impact on mental health in terms of a percent reduction in symptoms. Fourth, managers should seek data on the duration (the fraction of a year) the intervention will offer a sustained effect.

Multiplying these four numbers together will give managers an estimate of the potential cost benefit of an app per employee over one year. For example, $5,000 of lost productivity x a 25% reduction in depression scores x a three-month duration of effect (25% of a year) equals approximately $312 dollars per year. But if engagement is 5%, then multiplying $312 by 5% yields a value of approximately $16. We offer more details of the model and sample calculations in this published paper. Through the process of asking these questions and gathering relevant data, managers are simultaneously learning about their employees needs and how the digital mental health product may or may not help them.

While we have not yet seen apps offering a satisfaction or performance guarantee, managers should demand benchmarks for results and hold companies responsible for delivering on them. The best apps will not be afraid to sell themselves through results. As the space matures and companies merge, HR managers may soon be able to select customized app bundles and offer employers a suite of digital tools.

Decisions around digital mental health products for employees should be based not on marketing or their alleged popularity but on the evidence, engagement, and the types of therapists associated with the product. Except for telehealth apps offering a synchronous (i.e., video or phone call) connection to a licensed therapist or psychiatrist, they should be used only to augment, not replace, evidence-based care. And when choosing these digital products, HR managers should strive to identify their employees’ specific needs and find the offerings that can best address them.

McKinsey report predicts digital tools could be the answer to employee mental health crisis

Recently mental health has come into the spotlight, with rates of anxiety, depression and substance abuse disorder spiking during COVID-19 lockdowns.

It's no secret that employee mental health can take a toll on a business. However, a new report out of McKinsey said that digital tools could be one way to help support employee mental health and wellbeing.

"A mental-health condition manifests itself in workplace absenteeism, presenteeism, and loss of productivity," the authors of the report wrote. "The World Health Organization estimates that depression, anxiety disorders, and other conditions cost the global economy $1 trillion per year in lost productivity."

Roughly 24 in 100 employees require mental-wellness supports, such as counseling and psychotherapy, according to the report, and one in 100 will require acute care for mental health needs. The other 75 employees do require supports that foster mental wellness.

"A meta-analysis shows that for every dollar companies spent on wellness programs, their healthcare costs fell by approximately $3.27 and their absenteeism costs by about $2.73. With the ubiquity of personal digital devices – smartphones, fitness trackers, tablets, and so on – many wellness programs have moved to digital or virtual formats, which now account for the majority of employer-sponsored health offerings," authors of the report wrote.

The new report broke down three main groups of employee-wellness digital tools: wearables and digital biomarker apps, prevention and treatment products, and analytics tools.

According to the authors, wearables and digital biomarker apps allow employees to collect data about their condition in real time. These tools have secondary purposes regarding prevention, treatment and analytics.

Prevention and treatment tools are primarily focused on helping employees maintain wellbeing via a number of different avenues, such as chatbots or teletherapy. The tools are also used to help get employees the help they need at the right time.

Meanwhile, analytics tools can be used to help inform employees about their condition and about potential ways to mitigate stress. They can also be used to tell supervisors that their team is reporting stress. These could also help the leadership make decisions about employee wellbeing.

WHY IT MATTERS

Mental health is becoming a central focus in healthcare. In fact, more than 40% of U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with just 11% in the months prior to the outbreak, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

However, there is a shortage of mental health practitioners in the U.S. Increasingly, innovators are pushing to use digital to help tackle this gap and get folks the care they need.

"Digital solutions can offer therapeutic approaches or support positive behavioral change on a large scale," the authors of the report wrote. "They are accessible at any time and from anywhere, providing help on-demand without the long waits often needed for in-person therapy. They are also convenient, easy to use, and anonymous."

THE LARGER TREND

Today there are several companies working on mental health tools specifically for the employer space. In February Modern Health scored $74 million, bringing its total raised to more than $170 million for its mental health tool, which works with employer-customers to provide an app-based package of mental health benefits.

Lyra also created a behavioral health benefits platform for employers. In June, the company announced a $200 million raise, which raised its valuation to $4.2 billion.

Ginger is another big company in the space. Earlier this year, the company landed $100 million in Series E funding for its mental health tool. However, Ginger works with insurance companies and providers as well.

Across the pond, London-based Unmind raked in $10 million in Series A funding for its product that focuses on mental health in the workplace.